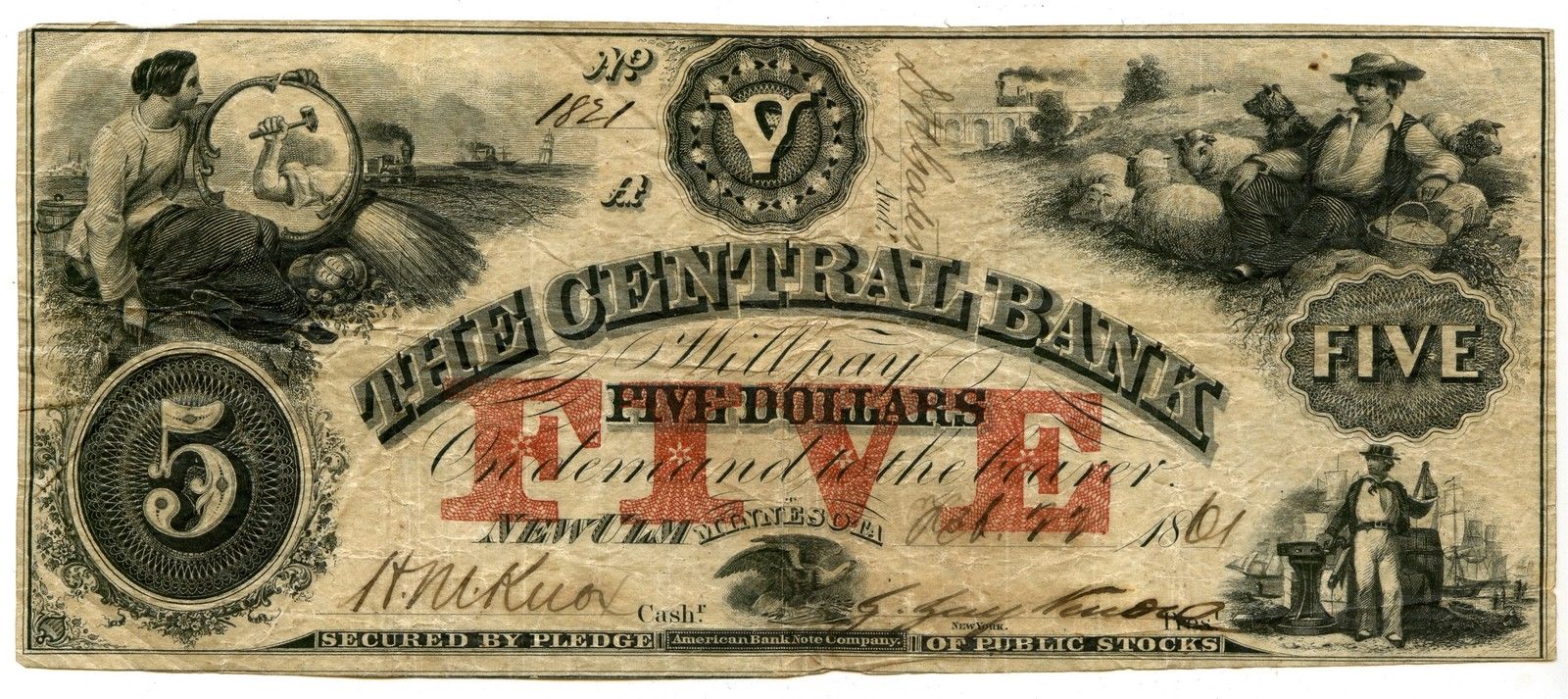

$5 Central Bank of New Ulm, Minnesota Surfaces

This landed in the mail today — and has rapidly become one of my favorite Minnesota bank notes.

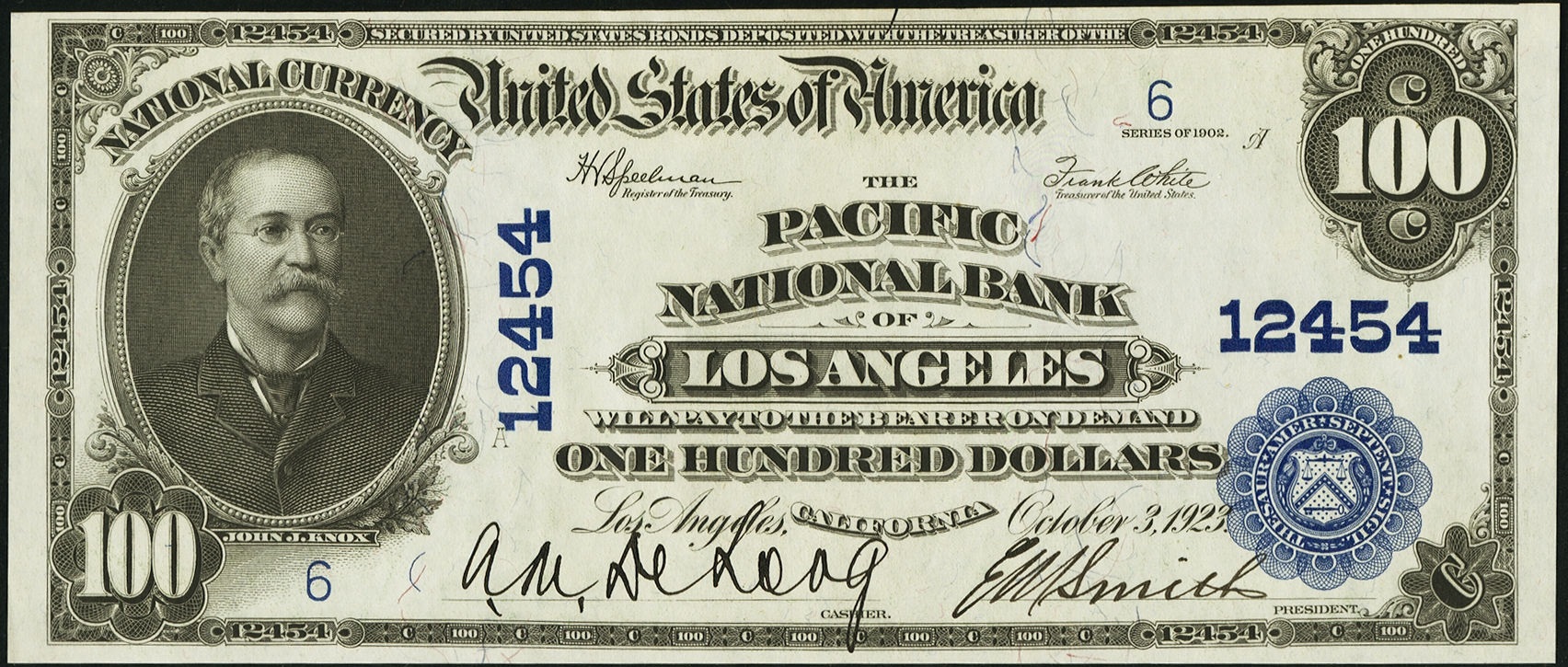

What makes this one special is that is signed by J. Jay Knox as president. Collectors of national bank notes will recognize him as the man depicted on Series 1902 $100 notes. Here is the story of John Jay Knox.

Knox (1828-1892) grew up in Oneida County, New York in the 1830s and 1840s. He was the namesake of his father, who was a successful merchant and banker. Knox earned a degree at Hamilton College in 1849 and worked at his father’s bank in Vernon, New York. In the late 1850s he and his younger brother Henry moved to St. Paul, Minnesota to take advantage of the opportunities available on the western frontier. With his father’s assistance, they established J. Jay Knox and Co., and became a prominent banking house in the city.

Knox learned first hand about the wild west nature of banking in Minnesota Territory. The territorial government banned the issue of bank notes, but creative bankers were easily able to circumvent the laws simply by endorsing the notes of otherwise worthless out of state banks. They hand-wrote an endorsement clause on the notes, signed them, and they became money. Knox was among the bankers to issue endorsed notes.

When statehood was achieved in 1858, among the first laws of the state legislature was an act to enable free banking in the state, with the privilege to issue currency. Notes were to be backed by the new Minnesota 7s, which were obligations of newly formed railroad companies. The bonds were thinly traded and did not have a ready market, yet they were accepted at 95% of face value as note security. Almost as soon as bank notes backed by these bonds were issued, they were heavily discounted in trade.

Among the new banks was The Central Bank of New Ulm, a town located about 100 miles from St. Paul. The Knox brothers purchased the bank from its organizers a few months after the bank opened. While the notes were floated in St. Paul, it is apparent that the remote location was deliberately chosen so as to reduce the likelihood that notes would be presented at the New Ulm office for redemption.

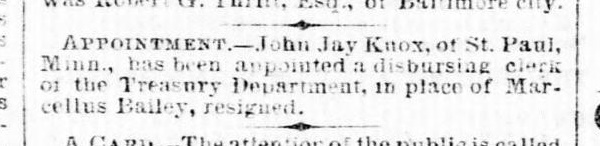

In February 1862 Knox wrote an essay that appeared in the Merchant Magazine and Commercial Review, a widely read trade publication, that supported Treasury Secretary Salmon Chase’s vision of a national banking system. The article was noticed by Chase, who made Knox an offer to serve in the Treasury Department as a disbursing clerk. Knox accepted the position in 1863.

Knox’s years of service was rewarded by being appointed Comptroller of the Currency, the top official who oversaw the regulation of national banks throughout the country, in 1872. He held this position until 1884, when he returned to the private sector.

The irony in all this is that Knox owned and operated the sort of bank that he decried in his writings in support of national banking. The Central Bank of New Ulm closed in 1862; its notes were presented for redemption, but Knox refused payment, and the state forced the bank into liquidation. The state auditor sold the bonds for a deep discount, leaving only enough hard money to pay bill holders 30 cents on the dollar for Central Bank notes.